- The ruined church of Saint Martin

- St Mary and St Martin: Churches and neighbours

- Traditional materials

- Looking after a ruin

The ruined church of Saint Martin

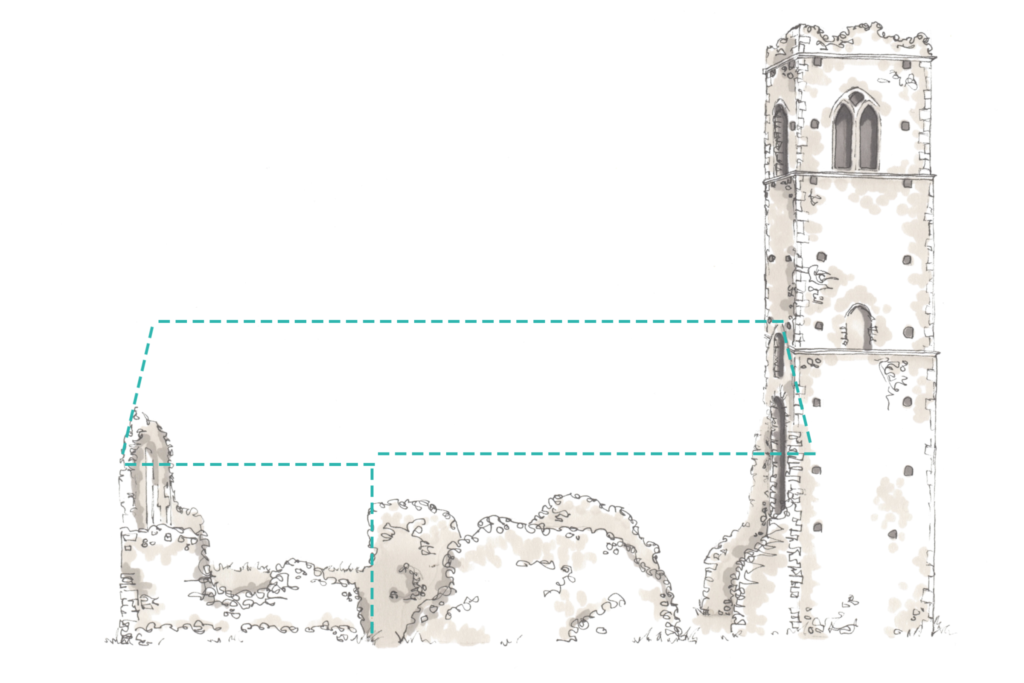

There has probably been a church on the site for over 1,000 years. If so, the first one was built of wood and rebuilt in stone in the 11th century. This sketch shows the ruin as it looks today; the dotted lines outline the roof as it may have looked like before the church became a ruin.

General view showing possible roof reconstruction

Four churches?

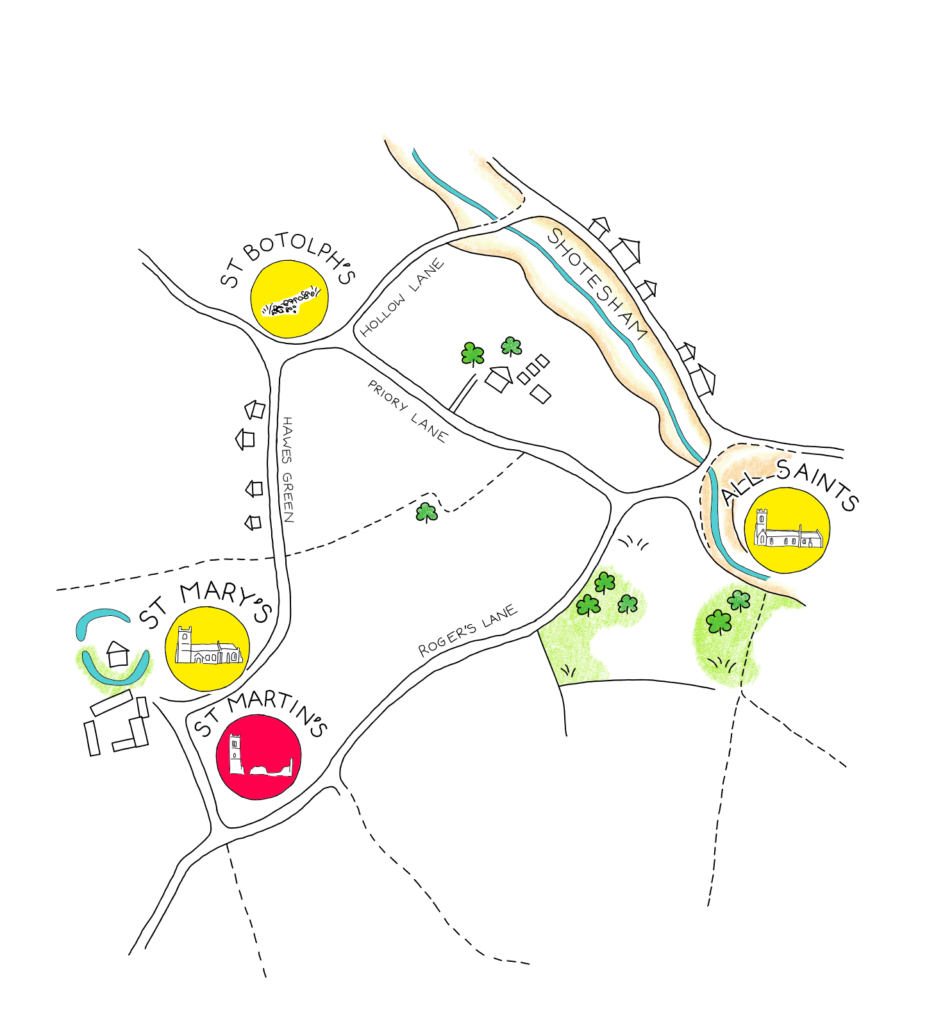

Many Norfolk villages have more than one church, but Shotesham is quite unusual in having had four. We do not know why, but it may be to do with the number of manors in the village. Two of the churches, All Saints and St Mary, are still in use. St Martin is a substantial ruin, and St Botolph has vanished except for a few pieces of stonework.

We do not know when St Martin fell into disuse, but it may well have happened by about 1550. This was probably because four churches were more than was needed for such a small village. The reason two of the four churches have survived is likely that All Saints served High Shotesham, while St Mary served Low Shotesham. The population of Shotesham in 1086 was about 650, and it is unlikely to have grown much over 500 years.

Map of the village

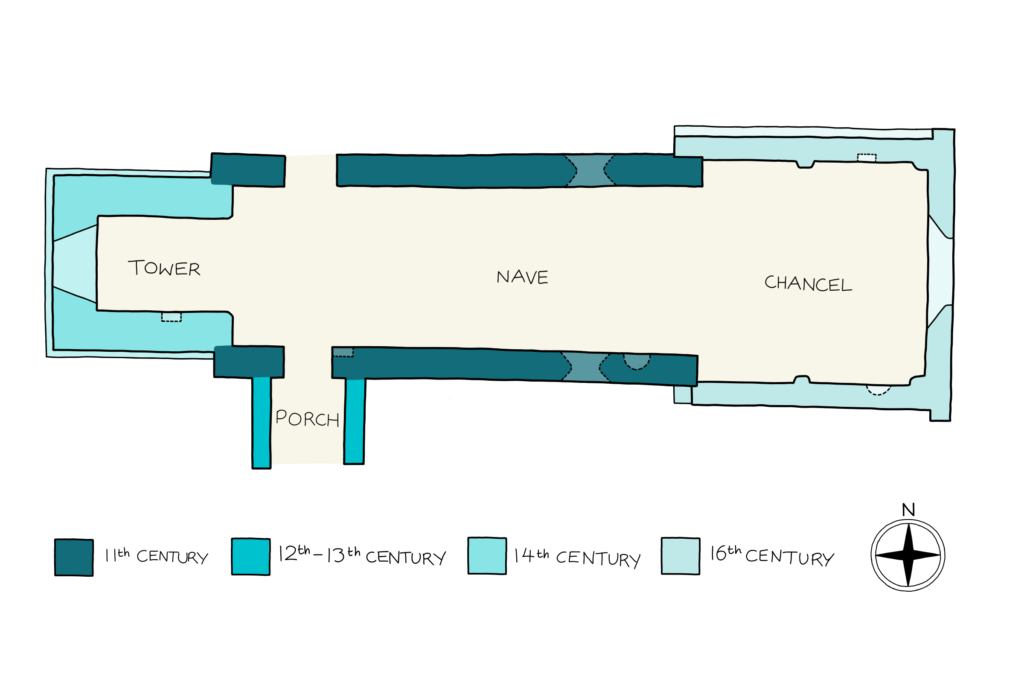

Development of the church’s plan

Despite the significant amount of remains, it is not always easy to say what the dates of the various features are. As the east end has been totally rebuilt, we cannot say with certainty what its original form was. The church had a nave, and probably a chancel, but it may have been a single-cell building. We cannot know if the east end was square or apsidal (rounded).

The porch was added later—possibly in the 12th or the early 13th century. At some point in the 14th century, the tower was added; this will have taken 20 to 30 years to complete. In the 16thcentury, the chancel was rebuilt. It is, unusually, wider than the nave, and it may indicate that a total rebuilding of the whole church was intended, working westward. If so, we cannot say why this was not completed. The abandoning of the project may have coincided with the church being closed.

Development plan

Features of the church

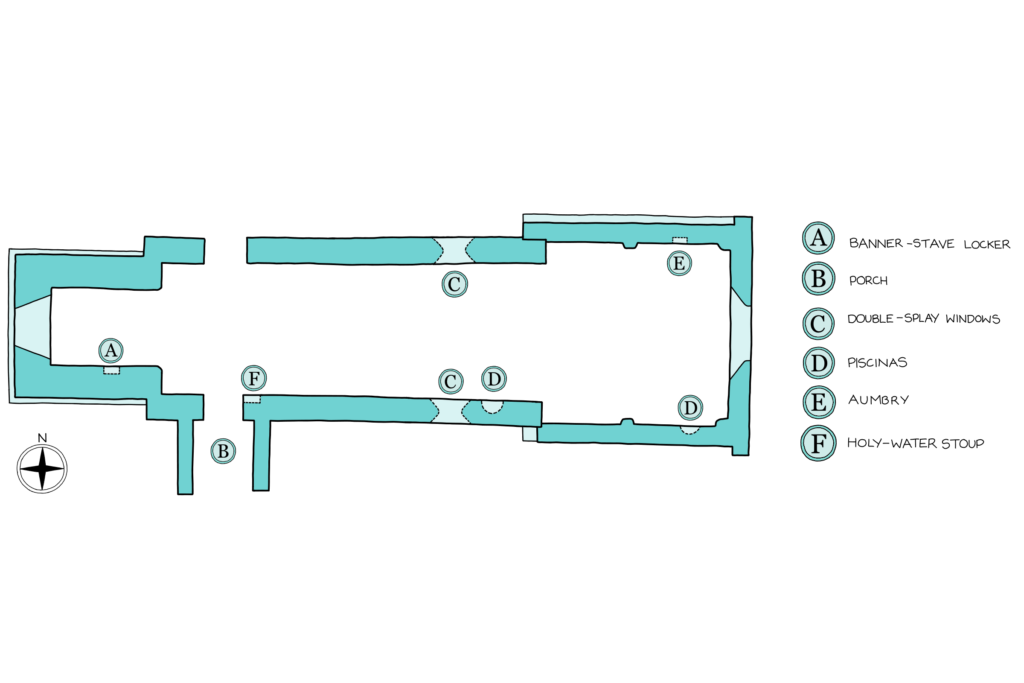

Church plan

Church plan

A. Banner-stave locker

This cupboard was used to store the long poles—or staves—on which processional banners were suspended, along with processional crosses. Not all churches have one, and their siting varies from church to church.

Example of a banner stave locker from All Saints Church, Shotesham (circa 15th C).

Example of processional banner: St Martin banner from Westminster Abbey.

Example of processional banner: St Martin banner from Westminster Abbey.

(Copyright: Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

B. Porch

Porches were more than just a shelter for the door. All the rites of passage—baptisms, weddings, and funerals—started in the porch before moving into the church. Secular business was also transacted in porches. Many have an upper room, called a parvise (from par vise – access by a vice or winding stair), though it is doubtful that St Martin’s did.

Example of a single storey porch from All Saints Church, Shotesham.

C. Double-splay window

This style of window, where the wall angles towards the window on both the inner and the outer side, is a marker of an early building date—10th or 11th century.

Example of double-splay window from St Michael church, Flordon, Norfolk.

D. Piscina

This is a basin in which the priest performed the ritual washing of his hands and the chalice during the mass. Piscinas can be simple or grand and are found by the sites of altars, so it is likely that this one served a side-altar in the nave.

Example of a piscina from St Julian church, Norwich, Norfolk.

E. Aumbry

This is a cupboard in which various items used in the service were stored, such as books and linen cloths. Valuable items, such as silver chalices, were kept in the parish chest under lock and key.

Example of aumbry with mediæval door in situ from St Peter Church, Great Walsingham, Norfolk (Copyright: Simon Knott)

F. Holy-water stoup

On entering a church, people dipped their fingers in a bowl of holy water, called a stoup, and made the sign of the cross as a reminder of their baptism. Such stoups are usually found in porches, so the fact that this one is in the nave indicates that the church did not originally have a porch.

Example of stoup from The Crypt, Blackfriars, Norwich, Norfolk

Who was Saint Martin?

The church is dedicated to Saint Martin, the 4th-century Bishop of Tours, France. He had been a soldier before he realised that such a calling was incompatible with a Christian life. He is supposed to have cut his cloak in half to share with a beggar.

Martin was a very popular saint, and a very ancient church at Canterbury is dedicated to him. His name has entered our folklore, as the fine weather we often have around his feast day (11 November) is called ‘St Martin’s summer’, and Martinmas Fairs were the traditional time for hiring servants for the next year.

There are over 170 pre-1800 churches dedicated to Saint Martin in Great Britain.

St Mary and St Martin: Churches and neighbours

Visitors to the ruined church of St Martin or the standing church of St Mary will wonder why the two churches are so close to each other: from one tower to another, a mere 120 m divides the two buildings. This is because St Mary and St Martin initially served two wholly different parishes and two separate congregations. Parishes were not divided up evenly according to population, and neither were the churches they served. That said, there is no obvious explanation for why the two parish churches should stand so closely together at their parish boundaries.

A view of the ruins in 1959 (courtesy of Jimmy Hazel)

The tower of St Mary

This strange density of churches is common in Norfolk and other parts of East Anglia. A nearby example of two separate parish churches actually sharing the same churchyard is found at Great Melton, where the shell of St Mary’s church tower stands immediately next to All Saints’ tower—like a pair of giant gateposts. More extreme still is Reepham, where two churches (Reepham and Whitwell) are physically attached to one another, and a third ruined church (Hackford) stands in the same churchyard.

There are many possible explanations for this mysterious phenomenon, such as the boundaries of many different manors falling within a small area, with each manor wanting to construct its own church. A more tangible explanation could be the low-lying ground of the region forcing churches to cluster together on bits of stable or higher land. Any or all of this may be the case with St Mary and St Martin in Shotesham; unfortunately, the documentary record does not allow us to say definitively what is true.

Who built and owned the two churches?

As well as relating to entirely different parishes, the twin churches of St Martin and St Mary also belonged to different institutions. The older of the two, St Martin, appears very early in the written record: it is listed in a charter granted by Edward the Confessor in 1046. From the 11th century, St Martin was one of the many possessions of the large abbey of St Benet’s at Holme, also in Norfolk. St Mary was, for much of its history, in the possession of a noble family called de Vaux, who are recorded at the time of the Domesday Book in the 1080s.

A legal dispute in the 12th century required interested parties to release their claims on the two churches. Abbot Ralph of St Benet’s at Holme relinquished St Mary, while the de Vaux relinquished St Martin.

Why is St Martin ruined? And when was it ruined?

Some authors have speculated that the destruction of St Martin’s church was a result of this monastic ownership, and that the church must therefore have been deserted since the Reformation in the 16th century. There is no evidence for this, and even if it was owned by an abbey, St Martin was an ordinary parish church—hardly a provocative monastic target. Indeed, other churches owned by St Benet’s at Holme did not meet the same end: the large church at North Walsham dedicated to St Nicholas is intact with the exception of its west tower (which only fell down in 1724).

Detailed accounts for both our churches only date back to the late 17th century. In none of these documents is there a single reference to the destruction or abandonment of St Martin. The earliest source of any substance for understanding the church is the churchwardens’ accounts, which date from 1690 onwards. There are no entries specifying repairs to either church building. However, although the accounts were originally intended exclusively for St Mary (according to the title in the pastedown at the beginning of the book), St Martin mysteriously appears on the following page. Was 1690 perhaps the year in which St Martin ceased to be a meaningful physical entity and became a mere legal formality? With no other evidence, this will have to remain an open question. The abandonment of the church must have been obvious to the inhabitants of Shotesham some centuries ago—so obvious that no one cared to make a written record of it. Its details remain a mystery.

Given we know that the two parishes were merged at some point, the proximity of their churches might to some extent explain the abandonment of one of the two structures. In the curious case of dual parishes with two churches in one churchyard, one thing is certain: few examples survived either the medieval or the early modern period. One of the two churches would eventually be abandoned as the dropping population density of an area forced the parishes to combine.

The building of St Mary

What is striking about St Mary is the large amount of brick in its south elevation. The brick seems to be inserted haphazardly, contrasting with the neat knapped flint of St Martin’s south side. Some of this material may well be original—there is very early brickwork embedded in St Martin, too—but it could also be associated with later repair campaigns. There is a 1609 reference to the dilapidation of St Mary, which may have required major works; a later programme is documented for the year 1775, where the whole roof of the church was rebuilt. The latter repairs involved a payment of fifteen shillings for 600 bricks.

St Mary’s south elevation

Elsewhere, St Mary has a late 14th-century core (the rather short nave), while the east end dates to the 15th century. The windows in the nave are a convincing Gothic design but were in fact created in a restoration campaign of the 1870s. The tower can be dated with some confidence to around 1535—the very beginning of the Reformation in England—as a gift of money is recorded for the building of the steeple.

The theme of brick continues in the interior of the church, where bricks form arches on either side of the chancel wall, reinforcing it with minimal material. This same technique was used at St Martin, where brick arches can be seen stripped of plaster, forming shallow niches. This use of bricks enables the walls to be rather thin, making them easier to pierce for windows.

Brick arches in the chancel of St Martin’s church

In general, although much more of St Mary’s church survives compared to St Martin, the former is characterised as much by later 18th and 19th century interventions as by medieval material. Just as we have to use our imagination to rebuild St Martin to something like its medieval appearance, so we also have to use our imagination to strip away what was added to St Mary.

Traditional materials

Flint

Knapped flint in the east end of St Mary

Flint is readily available throughout East Anglia. It can be seen dotting the surface of ploughed fields and at the side of roads. The material can, like rubblestone, be roughly bedded in mortar to create a wall, or alternatively ‘knapped’ or chipped into flat-edged, lustrous surfaces and used for infill. At St Martin’s church, the south facade designed to impress viewers was constructed out of knapped flint, neatly coursed. The rest of the walls are a more functional affair of flint rubble. Rubble or coursed flintwork often needs to be built with the help of wooden boards either side of the wall to stop it slumping while the mortar is wet.

When used in random rubble, flint masonry was generally intended to be rendered with lime and lime-washed to a brilliant white. There is some evidence of lime fragments under the east window of St Martin, indicating that the un-knapped flint sections were probably rendered in this way.

Brick

Handmade bricks were used from an early point in East Anglia, with some examples in the Blackfriars’ Hall in Norwich city centre dating from the 13th century. At St Martin, several sections of brick can be seen, both in the chancel and in the west end around the tower.

Lime

Historic buildings such as St Martin and indeed St Mary could not have been constructed without lime, a chemically versatile material which has been used since antiquity. ‘Lime’ here refers to the binding agent used to make mortars which set hard, enabling bricks, flint and stone to be bonded together. Lime is an umbrella term: through basic chemical processes, it can be transformed for various uses.

Limestone, that is the raw calcium carbonate (CaCO3) stone, is the first iteration in the ‘lime cycle’. It can be heated to 800 oC (or ‘calcined’) to form quicklime, calcium oxide (CaO). This reactive form of lime creates calcium hydroxide (CaOH) on contact with water, as well as a considerable amount of heat. The resulting calcium hydroxide is the mortar that can be used for building things. A quicker way to make the mortar is to start with quicklime in its dry form and then mix it with water and sand to make so-called ‘hot lime’-based mortar. Finally, if you premix quicklime with excess water and allow this to mature over a long time, a buttery solid called ‘lime putty’ is produced. This can be used for fine plasterwork and repairs.

Thatch

Many historic churches in East Anglia will have originally been roofed with thatch. Early churches, including the first phase in St Martin’s existence, would certainly have been thatched, since roof tiles were not available then. Thatch can be produced from a number of different natural plant fibres, including rushes and straw from grain production. In Norfolk, the Broads provided reeds that made ideal thatch. Thatch necessitates a steeply pitched roof: an unusually steep profile of a tiled roof is often a giveaway that the building was once thatched. St Martin is a good example of this: bricks embedded in the tower act as a ‘fossil’ of the gable end, demonstrating a steep pitch that would accommodate a thatched roof.

Other roofing materials

In East Anglia, roofing materials other than thatch were also used, typically terracotta (i.e. fired clay) ‘pantiles’ or ‘plain tiles’. Pantiles are S-shaped and overlap both horizontally and vertically. Plain tiles, on the other hand, are flat rectangular tiles resembling slates in shape and vertical overlapping. Real slates (typically from north Wales or Delabole in Cornwall) are rare in East Anglia due to the distance over land from the source of the material.

Lead would be used for ‘flashings’ (protective covers) around the bases of chimneys, or the ‘valleys’ where two roofs meet each other. On high-status ecclesiastical buildings, the roofs could be entirely clad in lead—a considerable expense. Many historic parish churches are dogged by the theft of lead, and the criminal damage resulting from it, to this day.

Timber

Before the Norman Conquest, most parish churches in England were constructed with timber. It is highly likely that the earliest version of St Martin’s church, referenced in the 1040s, was one such timber church. Greensted Church in Essex is a rare surviving example: it is built with split oak logs standing on end. This type of construction is known as a ‘palisade church’.

Looking after a ruin

Part of the historic value and significance of St Martin is precisely the fact it is ruined, representing the decline of a once denser settlement. Therefore, it is felt most appropriate to keep the building in a state of ruin, albeit a steady one. This has involved a considerable amount of clearing work, since in the 20th century the building was almost totally obscured by vines, brambles, and mature trees.

Video – The ruins at the end of the 20th century

The first recent clearing of the site was done between 2009 and 2012 by the parishioners of Shotesham. Funds were raised to repair an area of the tower where ivy growth had dislodged a large area of flint facings, exposing the core on the southwest corner. At the same time, repairs were undertaken to flints that had fallen from the ruined walls, and the churchyard was maintained in a different manner to encourage more native trees—more fruit trees were planted.

Volunteers clear away debris and roots from the remaining walls in 2011. (Courtesy of Mike Fenn)

Tower walls masonry in poor condition before the repairs.

In 2022, the PCC, with the assistance of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings(SPAB) and a number of volunteers, made further repairs to the building, rebuilding some very low sections of wall to stop people and animals jumping through them. This involved patch repairs using lime mortar and existing flints. ‘Soft capping’ was also used. This is where grassy turf is placed over the tops of walls, Although basic, soft capping is extremely important for the walls’ longevity. It protects the wall tops from frost damage and absorbs the water that would otherwise work its way into the walls washing out its core. The look and feel emulates that often associated with the romantic image of a ruin; this simple solution can make a long-lasting difference so that we can continue to enjoy this spectacular heritage.

View of the ruins in October 2022

This work was completed in November 2022 by a multidisciplinary project team including Domenico D’Alessandro, Glenn Gammons, Dr Nicholas Groves, Gethin Harvey, Michael Knights, Alfie Robinson, Beatrix Swanson.

Illustrations: Holly Rowland.

Project led by Shotesham Parochial Church Council, generously supported by: